Book review: Nineteen: 19 Insights Learned from a 19-year-old with Cancer

This review explores the recent book by Adam Robarts, about his son, Haydn, an extraordinary young man who was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive form of cancer.

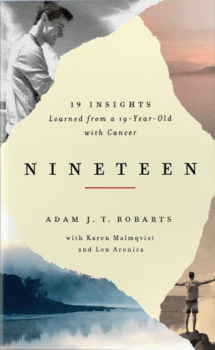

When most of my friends start recommending a book, I tend to pay attention. So it was with some interest that I read Nineteen: 19 Insights Learned from a 19-year old with Cancer, by Adam Robarts, an extended elegy to his son Haydn, who passed away from cancer one week before his 20th birthday. I thought of what a brave thing it was to do: write a book about what was undoubtedly one of the most grievous things that can happen to a person.

How does one find meaning in the loss of a child? We use the word ‘lost’ as a euphemism for death, perhaps in fear of the mystery that is such a passage, but one of the things that comes forth from this work is that Haydn himself taught his family and friends that death is not to be feared. I was fascinated that the author had chosen to remember his beautiful son in this poignant manner. This is not just a book about a boy. Written, according to Robarts, as “a self-help book of sorts,” it is a book that asks us to consider the purpose of our lives in this world from a broad spiritual perspective.

The poet Dylan Thomasurges us to “rage, rage against the dying of the light” but in Haydn’s case, and in his family’s case, there was no rage. There was an acceptance of the science, in that they did everything in their power to get the best treatment for Haydn, and there was a spiritual quest, a journey Robarts says revealed “Haydn’s depth of character, his fortitude, and a level of faith that I can describe only in words like profound, inspiring…heroic.” It is an opportunity to enter the unexpected, as a spiritually grounded, intelligent memoir of a short life, well-lived.

The book itself is organized around the extended metaphor of mountain climbing. Rather than work as a chronology, its chapters traverse a series of universal themes: acceptance, authenticity, positivity, hope, faith, prayer, nature, dreams, fear, detachment, calm, happiness, selflessness, mindfulness, trust, time, and finally, accompaniment. These themes map out the spiritual lessons learned as the family traversed this critical time together. In this way, I realized that every life has its unique distinctions, and part of the impressive nature of this work is that Robarts, from the position of a bereaved father, manages so eloquently to describe his son’s journey.

The book invites the reader to consider the deeper meaning of suffering, often through sharing questions that came up on their journey. In the chapter on accompaniment, using the extended metaphor of mountain climbing, Robarts says that he could have tried to carry his son up the mountain, but this would have ultimately been an act of selfishness, to avoid “the discomfort of watching another struggle.” It’s an important question: how does anyone, with all the love we have for one another, best assist a soul to make such a transition? It seems like this book offers a recipe for people facing this struggle, the transformation that life affords in preparation for a vast world to come. Haydn’s spiritual qualities shine in this book, and perhaps invite readers to shine, and struggle, along with him. This is the strength of the book, albeit the writing itself is engaging and accessible.

As Adam Robarts notes in the dedication, the purpose of Haydn’s life was “consciously bringing joy to others.” Like Haydn himself, the book doesn’t dwell on the tragedy of it all—although it doesn’t avoid it either—but rather, focuses on the profound lessons learned. Although Haydn passed away, this is a book of blessing, not grief, and will contribute to the spiritual growth of readers.

Public interest in the work has been broader than the Bahá’í community of which Robarts and his family are a part. The scope of the book is eclectic and brings in wisdom from many traditions. Those who are not familiar with the Bahá’í community but are interested in the spiritual progress of the soul will find much in this work with which to connect. The inclusion of thoughtful quotations before each section of the book provides ground for meditation; they invite people of different traditions to engage with the story in a deeply philosophical manner. The care with which Robarts has chosen these introductions is a testament to some of the conversations contained therein. Adam Robarts was a fortunate father indeed to have had such deep conversations with his son.

At its core, this book is about a family, and has a personal, connective legacy for me. Adam Robarts’ grandfather, Hand of the Cause of God John Robarts, and his wife, Audrey Robarts, encountered the Bahá’í teachings when those teachings were relatively new in Canada; they embraced the Faith in 1937, and raised their family as Bahá’ís. Adam’s father attended high school with my own father. They connected as young people independently investigating the truth of the Revelation and went on to spend their lives in its service. This book happened to come into my life while my father lay dying, aged 92. As I was saying goodbye to my dad, I was comforted by Haydn and his family, and had the opportunity to reflect on the deepest issues life can offer.

Robarts’ descriptions of his son add to my hopefulness about the potential of young people to create “an ever-advancing civilization.” As the same capacities present in Haydn become more prevalent, I feel the world is in good hands. Young people, religious or not, seem eager to understand the power of the soul. They, like my generation, still want to engage in spiritual thought and dialogue. This is comforting to me. Robarts invites the reader to reflect deeply on the meaning of life, in the end, this volume is a remarkable testament to the power of love.

-Heather Cardin

Category: Features