Canada’s Knights of Bahá’u’lláh

In its 30 December 2021 message, the House of Justice said that the Nine Year Plan “will make demands of the individual believer, the community, and the institutions reminiscent of the demands that the Guardian made of the Bahá’í world at the outset of the Ten Year Crusade,” inviting us to explore this history.

Central to the goals of the Ten Year Crusade (1953-1963) were the Knights of Bahá’u’lláh, consecrated souls who left their homes to open new territories to the Faith. This article was first published in the Summer 2019 issue of Bahá’í Canada.

The scope of the Crusade’s worldwide goals set out by Shoghi Effendi must have seemed staggering to the Bahá’í community back in 1953. One hundred and thirty-one “virgin territories” to be opened to the Faith!

Canada—a fledgling national community whose National Spiritual Assembly had been established only five years before—might have been excused for thinking itself to be too new to play a significant role in this global undertaking, but Shoghi Effendi’s expectations were great. His message to the Canadian Convention on 19 April 1953 unfolded the nation’s audacious mission. After congratulating Canada on the “triumphant conclusion” of its efforts during the Five Year Plan that was launched at the time of its emergence as an independent national Bahá’í community, the Guardian described it as the “prelude” to a “mightier undertaking.” This undertaking would focus not only on consolidating the “magnificent victories” that had been won on Canadian soil but also on inaugurating the “community’s historic mission” far beyond.

To this end, he tasked the community with opening “virgin territories” in North America and the Pacific, with consolidating the Faith in Greenland, MacKenzie and Newfoundland, with purchasing land for Canada’s first Bahá’í House of Worship and with doubling the number of Local Spiritual Assemblies. These were the “sacred strenuous tasks,” that the Guardian called on the community to “discharge nobly,” referring to the community as “worthy allies” and “chief executors” of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Divine Plan, from which the goals of the Crusade had been drawn.

Soon after that initial message, Shoghi Effendi emphasized that the settlement of pioneers in the virgin areas he had identified was of crucial importance and in this regard, Canada should not only feel responsible for filling its own goals, but Canadians should also pioneer to other countries’ goal territories if opportunities presented themselves. And this the members of the Canadian Bahá’í community—with support from their sister community south of the border—did with courage, persistence, and zeal. The names of the Knights who arose to fulfill the goals shine brightly in the annals of our history.

Many of the places where these modern-day heroes and heroines ventured have flourishing Bahá’í communities today. But back in 1953, the case was quite different. In fact, a letter written on the Guardian’s behalf admitted that “a few of the islands and territories embodied in the Plan are extremely difficult ‘nuts to crack.’” However, the community’s attempts to fulfill the goals before them continued unabated.

To the East

This was especially true of Anticosti Island in Quebec. Because it was a privately-owned island, it was almost impossible to settle there. It took three years of attempts by the National Assembly before Mary Zabolotny McCulloch secured employment on the island and won the title of Knight of Bahá’u’lláh for Anticosti in 1956. Unfortunately, she was only able to stay several months before she was forced to leave. She went on to spend 20 years in Baker Lake, Nunavut, where she and her family established the Bahá’í House and promoted the translation of the Teachings into Inuktitut.

St. Pierre Island, near Newfoundland and Labrador, was another particularly difficult “nut.” Ola Pawlowska, the Knight who pioneered there in October 1953, wrote of her arrival: “How to describe the feeling I had, flying to this speck of rock on the grey Atlantic? In a way it was as if a mighty wind had broken my earthly moorings and was carrying me on the wings of ‘be dependent on God alone.’… Here I was, an envoy from the Mighty King to this speck of land.” Treated as an outcast for two years, she was accused of being a spy and was often the subject of gossip. The locals eventually warmed up to her when she befriended a young boy and his family—although they were still not receptive to the message she had brought. After four years, with Shoghi Effendi’s permission, she departed the island but pioneered again to Africa for more than three decades. The Knights for the close-by Magdalen Islands, Kathie Weston and Kay Zinky, also encountered difficulties of health, isolation and discouragement in their pioneering experience, surmounting them through intense prayers that were answered with the appearance of seeking souls.

Prayer was a regular source of relief from the tests and difficulties that come with pioneering to new, unopened areas. Cape Breton was opened by four Knights of Bahá’u’lláh—two couples: Irving and Grace Geary, who were, by that point, seasoned by pioneering stints in other Maritime provinces, and Fred and Jeanne Allen, from British Columbia. Grace spent part of the first winter in a drafty cabin designed for summer visitors while Irving’s work kept him elsewhere. Finally, Grace decided that she could take no more: “I said the Remover of Difficulties over and over again. Inside of 10 days, Irvin’s work had been transferred…and by the beginning of February we had found a warm, comfortable apartment.” They remained on Cape Breton until 1961, when they were asked to return to Charlottetown, P.E.I., to maintain the Assembly there. Fred and Jeanne, who settled in a community about 80 kilometers from the Geary’s, supported themselves by opening a small grocery store—which gave them the opportunity to meet and teach people who came in. They remained on the island until 1962.

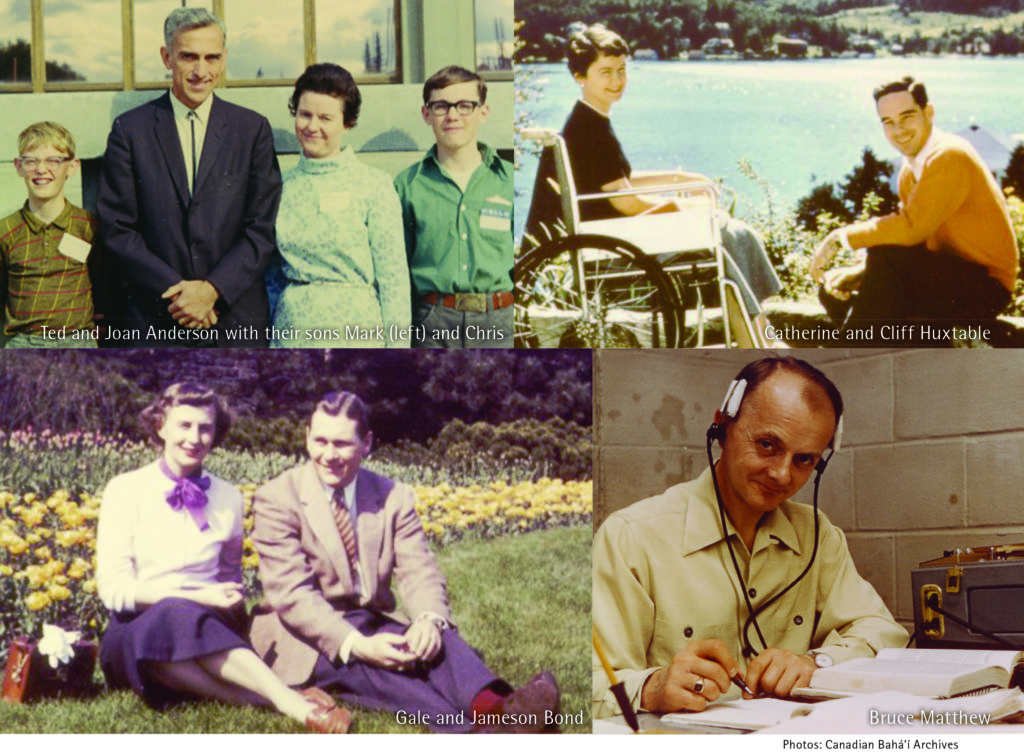

The Knights for Labrador, Howard Gilliland and Bruce Matthew, arrived separately in 1954, Howard from the U.S. to serve as a captain at the air force base in Goose Bay for about a year. Bruce—who had embraced the Faith in late 1953—also found work on the base, as a civilian, and remained until 1956. Teaching the Faith proved challenging in that environment and Bruce is recorded as lamenting, “Perhaps the Guardian will some day tell us why it is that people always wait until they have one foot on a train, boat or plane before they casually turn and ask, ‘By the way, what is this Bahá’í Faith?’”

Doris Richardson, Knight of Bahá’u’lláh for Grand Manan in Atlantic Canada, pioneered there in answer to the Guardian’s call in September 1953. Life was not easy, and patience was key to her service. It was four years before the first resident of the island embraced the Faith, which filled her with “supreme joy.” Doris lived to see the formation of the first Local Spiritual Assembly before her passing, still at her post, in 1976.

To the West

Doris’ sister, Edythe MacArthur, pioneered to multiple places in Canada before also becoming a Knight of Bahá’u’lláh. While Doris went east, Edythe pioneered to the Queen Charlotte Islands on the Pacific coast–and the opposite side of the country. As Hand of the Cause John Robarts put it, they had “covered the water fronts.”

The Knights of Bahá’u’lláh for the Gulf Islands, Cliff and Cathy Huxtable, arrived on Salt Spring Island in October 1959. To support the family, Cliff initially worked as a self-employed manual laborer but eventually became the vice-principal of a high school. He and Cathy, who suffered from muscular dystrophy, began hosting firesides in their home shortly after arriving at their post. Enrolments followed, and the first Local Spiritual Assembly of the Gulf Islands was formed in 1964. However, difficulties led to the Huxtables’ departure in 1965, after which they pioneered again to St. Helena, a 16-kilometer-long island, 2,000 miles west of Africa in the Atlantic Ocean. Cathy died there in 1967.

To the North

The day after they were married, Jamie and Gale Bond embarked on their epic pioneering journey to the District of Franklin in the Canadian Arctic in July 1953. The trip north on the icebreaker took two months, but they eventually arrived in Arctic Bay, where Jamie worked at the weather station and Gale served as the cook for the crew there. The bitter cold, the long hours of darkness and the close proximity of crew members with dissimilar personalities made service difficult, but the Bonds were undaunted. They remained in the District, living in different communities, until the end of the Ten Year Crusade.

Another pair of newlyweds who embarked on their northern pioneering venture to win the title of Knights of Bahá’u’lláh were Ted and Joan Anderson, who arrived in Whitehorse, Yukon, in September 1953. When they got off the train, a fellow passenger advised them, “‘If I were you-all, I’d get right back on board this train and head south!’” But they had a mission in mind and refused to be perturbed. Instead, they carried some of their suitcases a block down the dusty Main Street to a hotel. Ted wrote, “For $7.50 a night we got a room without a bath—and, as Joanie noted in her diary, ‘PRAYED LIKE MAD!’” The Andersons survived the bitter winter and the following spring received a letter from the Guardian, with instructions: “He urges you to concentrate on the native population, as it is for that reason that we have opened new countries to the Faith. May you be confirmed in this teaching effort…” The community grew, the first Local Spiritual Assembly was elected in 1959, and teaching efforts among the Indigenous believers led to further growth, as new believers arose with enthusiasm, dedication and wisdom to teach their families and members of their communities. By the time Joan and Ted left the Yukon in 1972, after 19 years of service, there were some 400 Bahá’ís, many of them indigenous. Their efforts had, indeed, been confirmed.

In the District of Keewatin, Dick Stanton won the distinction of Knight of Bahá’u’lláh in the tiny settlement of Baker Lake, which had only about 100 residents at that time, remaining there for some five years. His initial work was later nurtured by Mary Zabolotny McCulloch and her family.

To the South

In a much warmer clime, a pioneer from Canada, Gretta Jankko answered the Guardian’s call to become the Knight for the Marquesas Islands in the Pacific, administered by France and the “least known virgin goal assigned to the Canadian Community.” While life was outwardly primitive, Gretta wrote, “All the time on those islands I was very happy. I loved the people and we were very close to each other; they asked me many times not to go away from the islands.” While she overcame difficulties with obtaining visas to remain at her post, she was forced to leave after an attempt on her life in 1955. The authorities told her they could not guarantee her safety and she left to continue her service in Finland.

Also distant, though in an entirely different direction, the South African homeland of Bechuanaland (now Botswana) was the pioneer post where John, Audrey and Patrick Robarts won the honour of being named Knights of Bahá’u’lláh. At one of the Intercontinental Teaching Conferences held to launch the Crusade, John and Audrey became excited about the idea of pioneering and wrote to Shoghi Effendi, suggesting that they would go to the Yukon, Labrador or Iceland. His response must have come as quite a shock to them: “Bechuanaland highly meritorious.” So rather than north, they headed south, arriving at their post 16 weeks later. By 1957, the same year that John was appointed a Hand of the Cause of God, the first Local Spiritual Assembly of Bechuanaland formed in Mafeking, and the family relocated to what is now Zimbabwe, where the first Local Assembly was established the following year. They remained in Africa until 1966. When Audrey returned for a visit many years later, the National Spiritual Assembly greeted her as “Beloved Mother of our country.”

Our Task

The stories of these “quickeners of mankind” who set out to win the goals of the Ten Year Crusade for Shoghi Effendi—in spite of their own self-doubts, the loneliness they felt and the physical hardships and opposition they faced—serve as a potent reminder of the power of sacrificial effort. It is, in large part, because of them that we are where we are today. As the House of Justice wrote in its 26 March 2016 letter to Canada and the United States, “Your sister communities, so many of which you helped to establish, are now mature, and you stand with them ready to take on the sterner challenges that lie ahead. The movement of your clusters to the farthest frontiers of learning will usher in the time anticipated by Shoghi Effendi at the start of your collective exertions, when the communities you build will directly combat and eventually eradicate the forces of corruption, of moral laxity, and of ingrained prejudice eating away at the vitals of society.”

These heroic Knights, along with other early teachers and pioneers, opened the “virgin territories” to the Faith. That was their work, their glory. Our task now is to extend the spiritual path they blazed, to deepen the conversations and relationships in the villages and neighbourhoods of those places as we reach out to the “widest possible cross-section of society and to all those with whom [we] share a connection—whether through a family tie or common interest, an occupation or field of study, neighbourly relations or merely chance acquaintance,” as the Universal House of Justice wrote, “so that all may rejoice in the appearance, exactly two hundred years before, of One Who was to be the Bearer of a new Message for humankind.”[1]

– Ann Boyles

This article draws on the book The Knights of Bahá’u’lláh (George Ronald 2017), by Earl Redman, for its source material.

[1] From the Universal House of Justice to all National Spiritual Assemblies, 18 May 2016.

Category: Stories